Limpkins! (Aramus

guarauna)

This

page started 04/01/2022 from material I posted earlier on other

pages. Rickubis designed it. (such as it

is.) Last update: 03/29/2023

Images

and contents on this page copyright ©2021-

2023 Richard M.

Dashnau

Go back to my home page, Welcome

to rickubis.com

Go

back to the RICKUBISCAM

page.

I

was introduced to Limpkins when I heard about their appearance at

Brazos Bend State Park. I learned that they probably followed the

invasion of Apple Snails (Pomacea sp.)

across the Southwest states

until they appeared in Texas. I learned about and saw Apple Snails

first, and the information I've gathered about them is on my Snails

Page. I've

learned

that although the circumstances which brought the Limpkins here isn't

so good (invasive snails), the fact that we can watch them in different

places, here in Texas, is

really amazing.

It appears the Limpkins have only been here a few years so

far.

So, I'm collecting my images/videos here so others can see them. The

latest additions will

be at the top of the page.

03/19/2023

A

cold front had passed through recently. That morning, the thermometer

in my car showed 47°F. I

didn't bother trying to record the

air temperature on

the trail because I was

trying a new piece of equipment that I thought

would give me related data. I can say that it felt REALLY

cold

out there. Limpkins

were first reported in Texas in 2021. They've been hunting

in Brazos

Bend State Park since then, usually around Live Oak Trail (and the

property next door) during the Summer. When

Live Oak Trail dried out last year, the Limpkins stayed near the

lake

next door to BBSP, but a few foraged in Elm Lake.-which is about 1/2

mile from where the Limpkins were on Live Oak Trail.

I've watched them in this corner of the lake, and found out

they were eating mussels.

Limpkins

are "mollusk specialists", and are adept at opening many types of

shells. I was happy the first time I got to see a Limpkin eat a mussel

a few weeks ago. On this day, I watched this

Limpkin capture at least

6 mussels over 45 minutes, and was able catch some of that on video.

That's what will show here. The Limpkin was hunting

along the near bank of that island across

the way (about 50 yards

from this trail). When the Limpkins hunted along Live Oak Trail, they

probed with their beaks, similar to the way Ibises

do. It seemed to be mostly blind probing in

murky water with

dense vegetation. But this one seemed to be hunting with its eyes,

visually inspecting the water, similar to Herons or

Egrets. the frequent probing at Live Oak Trail. Pictures

and

video clips of the Limpkins on Live Oak Trail are on further down on this page.

I

caught multiple videos of the entire process-from capture to cleaning

the last morsels out of the shell. The procedure as I saw it:

1)Hammering at the mussel-this seems to be aimed at the

outer edges of the closed

shell, possibly to chip off the edge so the beak can be pushed in.

2)Standing the shell and trying to push the beak between the halves. 3)

Once part of the beak is in,

move it around to disrupt the mussel until

both jaws get in so that the shell-closing muscles can be cut. 4) Now

the mussel shell lies open. Time to

snip the good parts away from the shell.

Small bits are pulled from the

shell and tossed, although a few are swallowed. 5) The main body is

pulled out, shaken a bit, then swallowed without ceremony. 6)

A bit more cleanup of the shell

and surrounding to pick up any missed

scraps, and then off to hunt for the next one. Someday I

might

pull frames from the video to illustrate that procedure here, but not

today. For now, it's

visible in the

edited video. By the way, note all of the discarded

mussel shells in a few of the

pictures below. Wow! So, even though the day was cold, damp,

gray

and pretty miserable-it was

worth going out on the trails that day.

On 01/15/2023

I

was at BBSP, and it was an interesting day. Herons and limpkins!

At 11:00, one of the park

visitors pointed out that a Limpkin (Aramus guarauna)

was foraging near an

island in Elm Lake.

I'd have never noticed it otherwise, since a group of Black-bellied

Whistling Ducks were lying around and swimming there, and the Limpkin

was among them.

The Limpkins had been hunting along Live Oak Trail through 2021 and 2022. They seemed to leave that

area during drought in the Summer of 2022, and one was seen briefly in

Elm Lake then.

I

was happy to see this one, and wondered if it would get lucky, since

they prefer to eat molluscs. The Limpkins have moved into

Texas

because of large numbers of Apple Snails (Pomacea sp.)

that have

appeared here. To our knowledge, there are still no Apple Snails in Elm

Lake (no egg cases visible). But the one seen in Elm Lake in

2022

was eating mussels. And...this Limpkin

found a freshwater mussel, too!

The

Limpkin's meal remained partially hidden by a bump in the ground. I was

happy to see the process anyway. The images below are frames from

video. The

edited video is here .

From BBSP on 05/29/2022

For now, more Limpkins. As usual, lots of things were going

on

out at the park. I spent about an hour on Live Oak trail, and watched

the

Limpkins. Conditions along that trail have been getting dry over the

last few weeks, so the Limpkins were foraging at least 25 yards away

from me--although they were North of the

trail. That is, between Live Oak Trail and the Park Road.

This video link will let the

viewer spend about 4 minutes with some of the Limpkins I saw.

As

noted elsewhere on my pages, during dry times Apple Snails (Pomacea

sp.) can aestivate by burrowin into the mud. One study showed that they

could live that way for 10 months.

One

of the snails that was retrieved by a Limpkin was covered with mud (I

didn't recognize it was a snail at first). Perhaps it had

been

trying to burrow. No--not the one in the image below.

On 4/10/2022, I'd

signed up to lead a hike and other tasks, so I went out to LIve Oak

Trail early to look for Limpkins. I got to watch some, and here are

the images. I

still haven't caught close shots of Limpkins dissecting snails, but

there is some of that shown at distance in the video I got. There are

also a few closeups of the Limpkins'--and

Ibis'--dipping behavior while foraging.

I believe that "dissection" is an appropriate term for what the Limpkin

is doing to the snail. When viewed in realtime, movements are so quick,

that

the quick twisting and flicking doesn't reveal what is

happening. But if the video is slowed down, then it's possible to see

that the Limpkin is using its beak with precision, and is tweezing

away

small bits of snail flesh, and then tossing them aside. In the slowed

video, some of the bits are visible, and some may be pink. I believe

that the Limpkin is rejecting bits based on how

they taste. In the

video I captured, bits were snipped and tossed...until one bit was

pulled off and eaten. The rest of the carcass was eaten right after

that. The edited video is at this link.

Also, if pictures of one

Limpkin is good--then a picture of two Limpkins must be better! So,

they're here, too.

Many folks

describe a Limpkin as being about the size of an Ibis. Today, a White

Ibis (Eudocimus albus) foraged

next to a LImpkin, so I got some direct comparisons. The two birds

foraged

next

to each other, and I could watch them both probing for food with their

beaks. Clips of them foraging together are also in the edited video.

From BBSP on 04/03/2022. More

with the Limpkins! I was on Live Oak trail

around 8:30am. There weren't very many Limpkins active there yet, but I

did see a few.

One

was calling from a tree across the lake that is outside the Southern

boundary of BBSP. I shot video of that to show how far that sound

carries. About 30 minutes later, The

Sun started

breaking

through the clouds, and more Limpkins began hunting North of

the

trail. I was briefly distracted by watching a Great Blue Heron hunting

successfully, but returned to the Limpkins

for these images and

video. The images below are a mixture of still photos and

frame grabs from the video clips. The video clip is here.

I

was able to get some nice close views of Limpkins hunting, but a clear

view of the Limpkins breaking into the snail still eluded me.

I

also found this report on line:

"Natural

selection by avian predators on size and color of a freshwater snail

(Pomacea Jagellata)" 1999 by Wendy L. Reed and Fredric J. Janzen.

The research was done in Costa Rica,

but

involved Snail Kites and Limpkins. The predation was on Apple Snails,

but a different species. Size and behavior of the snails seems to be

the same as our problem P. maculata though.

Among

points in the report I found interesting: 1) Snail

kites rely on visual cues while hunting by

flying

slowly across a marsh or hovering while searching for snails. Limpkins

rely on tactile cues

during

foraging by probing beneath vegetation and on the bottoms of marshes

for apple snails. 2) Individual Limpkins differed in the size of snails

they consumed, and in their choosing to

puncture

shells before consuming snails. No single foraging pattern is

exhibited by all Limpkins in this study area. 3) As snails age and

grow, they change their vertical distribution their primary

behavioral

defense against predators. Large apple snails spend more time at the

water's surface. The change in size is accompanied by changes in

behavior. Larger snails respond to

mechanical

disturbances by dropping off vegetation and burying themselves

in

the substrate quicker than small snails do. 4) Limpkins may

prefer snails of average size due to decreasing

energy

gains at either end of the snail size distribution. Limpkins were more

likely to puncture shells of large snails compared shells of small

snails. This shell-puncturing behavior suggests

that

large snails may be more difficult to handle, requiring additional time

and energy to puncture the shell and obtain a meal. The optimal prey

size for Limpkins might then be those snails small

enough

not to require a hole to procure a meal, but large enough to provide a

worthwhile effort.

The

report added a bit more perspective to some of behavior I've recorded.

I can see how a Limpkin might have a harder time "pincering"

a

large snail in its beak and carrying it, so puncturing

it would make

it easier to carry. But I've seen that the Limpkins have carried the

shell out of the water and to a solid base to give support the snail

shell during the stabbing attack. I think piercing

the snail weakens

it and the muscles holding the operculum closed, and allows the Limpkin

to get under that "trap door" to tear it off. In one of the

other

clips from this day, I show what happens

with a really small snail

(three images below right). The Limpkin set it

down,

prodded it a bit (and it was too small to get a beak tip into) then

tried to smash the snail with the tip of its beak. The

snail was knocked into the air and fell in the water and was lost to

the Limpkin.

A bit

later, the Limpkin found a larger snail. The snail was carried to a

more solid platform. .

I

could see the Limpkin working on the hidden snail. It alternated

delicate probing with hard stabbing. Movements changed as the

snail's body was exposed. There was vigorous rapid movenents

of the

beak as the snail body was pulled free. Viewed in realtime, the

movements are very quick, and barely noticeable, but with slowed down

video, the amount of movement is impressive.

What was being shaken

free? Was it shell fragments, detritus, maybe the toxic yolk

glands? I can't identify the fragment the seemed to fly off the snail

as it was being shaken.. The Limpkin

didn't immediately swallow

the snail either. It tossed the meat to the back of its beak, seemed

about to swallow--then spit it up and shook it a few more times before

swallowing it. Finally, I

caught a quick view of a Nutria "photo bombing" the scene. Again, The video clip is here.

Update 04/01/2022 - From BBSP

on 03/27/2022.

I'd last seen Limpkins on Live Oak trail last October (2021). Since

then, less Apple Snails (Pomacea maculata) and egg masses were

observed

on or near the trail. Over the winter, no snail eggs appeared

on

Live Oak Trail so I stopped going there because I thought the Limpkins

wouldn't be active. Sometimes I could

still hear Limpkins

calling from this area even while I was at 40 Acre

Lake. The lake just across the

South park

boundary contains the main snail infestation. With the warmer

weather,

I checked the trail for snail eggs. No egg masses

yet, but the Limpkins were around. Two Limpkins were resting

on

top of the floating plant mats about 40 yards away, along with a few

scattered

snail shells. I watched another one as it hunted. This was

the

first time I got to see the Limpkins foraging! Widely-splayed toes help

distribute the Limpkins' weight as they stride on

floating plants.

Their constant probing for prey reminded me of the similar

behavior of Ibises. Success! Jackpot! A big snail was discovered as

turtles and I watched. The Limpkin moved to a firm

surface so it

could pierce the snail. It placed the snail, then attacked it with

short, accurate and powerful strikes. Most of the images here are

frames from the video clips I shot.

The video clip is here.

I've

tried to pierce Apple Snails by stabbing them with the point of a

smooth flounder gig. The shell is round and hard--and

difficult

to pierce with a single point. If the point wasn't thrust just right,

it

slid off the shell, and the snail rolled away. But this

Limpkin

was an expert, and pierced the shell after a handful of hits.

I

was not close to the Limpkin, so couldn't get a great view of its

technique.

There's a a bit of manipulation needed to get the

snail out of the shell. It's interesting that the feeding

strategy doesn't include shattering the shell into pieces.

There

was rapid back and forth

head-twisting motion, just before the snail is taken out. And then the

end of an invasive snail.

Even

with wide feet, the Limpkin was too heavy for some plant mats. It

continued working as it sank into the water, then hopped to the next

mat. I saw this Limpkin eat at least 5 snails in 30

minutes.

The probing seems to be random. How can a Limpkin tell when it has

found a snail? It must be contacting other hidden objects, sticks,

etc., with its beak. But it seemed to ignore

them in these

very quick contact probes. But with positive snail contact,

the

Limpkin starts working at the snail. One snail took

more

effort, and the Limpkin had to do a lot of twisting to get it

out of the plants. What was the snail holding on to? The

Limpkin seemed to be a bit surprised,. Again, The video clip is here.

The

egg masses of Apple Snails (Pomacea sp.) are toxic. The

glands

that provision the snail eggs (albumin glands) inside the snail are

also toxic.(more details are on my Pomacea

Page).

There

are multiple reports that describe how the snails' predators discard

these glands. ( since Oct. 2021 I've found more reports that describe

this behavior) Discarded glands have been

seen in snail detritus

left by Raccoons. (Observations of Raccoon (Procyon lotor) Predation on

the Invasive Maculata Apple Snail (Pomacea maculata) in Southern

Louisiana by J. Carter et. al (page N15.)

Removal of these glands by Limpkins is mentioned in " Defenses of the

Florida Apple Snail Pomacea

paludosa by Noel F. R. Snyder and Helen A. Snyder

(1971)(page 177)" and by Snail Kites in

"Mollusk Predation by Snail Kites in Columbia Noel F. R.

Snyder and Herbert W. Kale" 1982 (page 97)

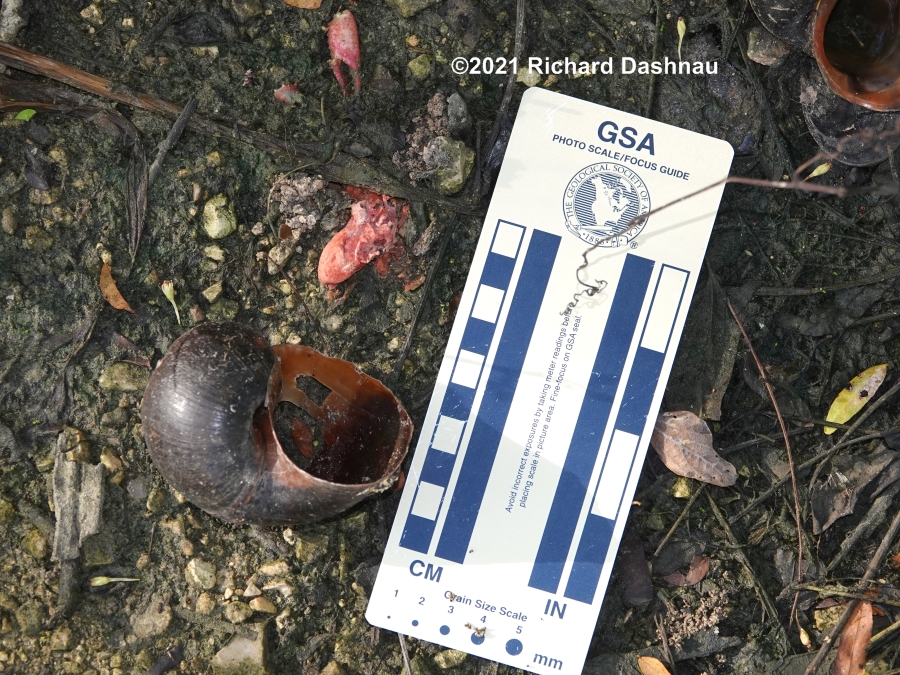

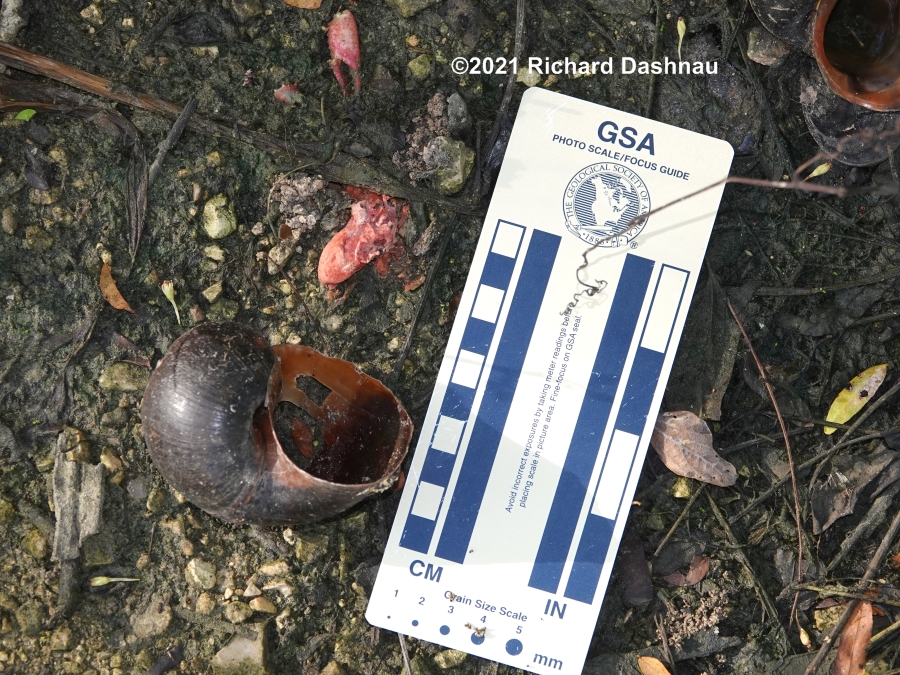

Nothing

pink showed in the meals I watched, but that is inconclusive.

They could have been hidden inside the body. I took the

last picture on Live Oak trail in 2021. The shell shows twin

punctures,

which are evidence of Limpkin predation. The pink mass

above the shell is a discarded albumin gland. I hope to catch

this behavior on film.

The snails are still here in the park. It was

great to finally see Limpkins hunting; but bad news that

there

are so many snails inside

BBSP.

Update 04/04/2022 - From BBSP

on 10/24/2021.

On Live Oak trail October 2021. I was still trying to see more

Limpkins, and hoped to see them foraging. I also hoped to see any other

animals-Alligators,

or Raccoons-going after the Apple Snails, but no luck there.

I

did see and hear this Limpkin, and the call was not the "crying" sound

that I'd hear before. I recorded the call.

Since then, I've learned

that Limpkins have different calls (like other birds do) and this was

probably a female Limpkin. I got the call on video, and The video clip is here.

07/25/2021 and 08/01/21- I've

been doing more research on our apple snail invaders since July. When I

saw the inside of an adult Pomacea, I noticed orange masses or organs.

I

figured that those were eggs. Since the deposited egg masses are toxic,

I wondered if the eggs inside the snail were also toxic. And, if the

eggs are toxic--how can any animals

--such as Limpkins--eat the

adult snails? After a lot of searching, I couldn't find any

detailed description of how this situation is dealt with. The

first picture below was

taken on 7/24/21, but I'd seen inside other

snails before then. The other two pictures were taken

7/10/21,

and show a snail that something had eaten. At the time, I hadn't

realized that the toxic egg masses had been left inside the shell.

I found a number of references saying that animals that eat the snails

discard the albumen glands. But the only predator I saw named doing

this was Snail Kites. But no clear descriptions.

I started searching for proof that Limpkins

might discard these organs. I found a video on youtube that shows a

Limpkin doing this! After that, I started looking around BBSP

for

signs

of this behavior.

But let's pause a bit.

Limpkins? Limpkins (Aramus guarauna) are long-necked wading

birds

with long, pointed beaks. They're about the size of Night Herons (maybe

a bit larger).

According to Avibase, the World Bird Database,

it is the only extant species in the genus Aramus and the family

Aramidae. The "home range" of 4 subspecies of Limpkins is: Florida,

Cuba,

Jamaica ; southern Mexico south to western Panama;

Hispaniola and Puerto Rico; central and eastern Panama; South America,

south west of the Andes to western Ecuador, and east of the Andes

south

to northern Argentina. Like many wading birds, Limpkins can be

generalist predators but according to many sources, the greatest

component of their diet is: Apple Snails. If we examine the

list of regions in their "home range", we can see something

missing-- TEXAS.

That's right. In fact, their home range is far from

Texas.

Texas

is now being invaded by Apple Snails. If only Limpkins were

in

Texas! Well...they ARE in Texas. In fact, they have been

hanging

around in the lake next door to BBSP for some months

now.

That

lake is infested with snails. Unfortunately, the snails have made their

way to the BBSP side of the fence, along Live Oak Trail. But the

Limpkins have been picking them off there, also.

Discarded

snail shells litter the trail. I went down Live Oak Trail on 7/18, and

I saw something interesting among some discarded shells. I took a few

pictures. Next to one

of the shells is a pink mass. I think that

mass is one of the "albumen glands" that was discarded by the Limpkin

that ate that snail. The trail was really wet, so I didn't go further.

First

3 images below show shells on the trail, and a pink mass neer them. The

last image was taken there on 8/1/21, and shows pink material in the

discarded shell.

I

returned to Live Oak Trail the next week (7/25). I'd been

around

the other trails, and entered Live Oak from the East end and walked

West. I was doing snail egg removal. It was Noon,

and it was

hot, so I didn't expect to see anything. A Limpkin appeared

on

the South side of the trail, near the fence, and hunted the area near

the fence. I stayed back, and hardly moved.

It came to

the trail, walked on it a bit, then went back under the fence and

eventually up the levee and across. I got pictures and a bit

of

video! This is all edited into this video.

Next

weekend (8./01). I'd been out on the other trails first. I met a couple

park visitors I'd sent to Live Oak trail and they told me they'd hadn't

seen any Limpkins, but had seen snail egg masses,

and even a

few live snails. So I was on Live Oak Trail again, at about

12:30pm. I'd gotten almost to one of the "bridges" when I saw

a

Limpkin up in a tree between the trail and the

road--that is,

North of the trail. I watched it for about 20 minutes, until thunder

from approaching rain clouds convinced me to start back to my

car. I got a brief look at another Limpkin

in a tree near

the one I'd been watching. They both moved, and seemed to

start

hunting, but I didn't want to get caught in rain that seemed to be

approaching. I got photos and video

clips. Again, this has all been edited into this video.

And,

I found another snail shell that seemed to have remnants of a discarded

"albumen gland" in it. I also found another paper that seems

to

have been inspired by the habit of snail predators

discarding the

"albumen gland": "Apple

Snail Perivitellin Precursor Properties

Help Explain Predators’ Feeding Behavior" 2016 by Cadierno, Dreon,

Heras. While it discusses Pomacea canaliculata and

not our

problem (P. maculata), I think it's still related. This study is where

I got the term "albumen gland" for the organ which produces the snail

eggs. Perivitellin

serves as a nutrition source for snail

embryos

(similar function to egg yolk ). While the paper is a bit technical for

me to fully understand, for me it verified: a) that

the

organs are

toxic, and therefore consumption of the entire snail

could be dangerous; b) that experienced predators do

discard toxic parts of the snail, rendering it safe to eat. From the

paper: " Therefore,

as the noxious perivitellin precursors are exclusively

confined

within the AG, this explains why it is the only usually discarded

organ, even when this behavior implies a large loss of the total energy

and nutrients available from the soft-body biomass

(Estoy

et al. 2002). Finally, we propose that the reddish-pink gland color may

contribute to this behavior, helping the visual-hunting predators of

adult snails to associate the bright AG color with the

noxious compounds it

carries."(page 466 "AG"=albumen gland)

This could be trouble for our local predators (such as alligators) that

might consume entire snails. Raccoons might be able to

identify

and

remove the glands, but they'd have to learn about the danger first

(that might be what ate the snail in the picture above).

It's potentially good news that Limpkins are eating snails here. It

will

be

better news if they establish a breeding population in

Texas. They can help control the spread of the Pomacea. But, regardless

of predation, and it seems to me that the snails will remain.

I

think

the

most we can hope for is that the predators that have followed the

snails (and other local predators) and the snails will reach a

"balance" where the snails will not overpower the environment.

There

must be reasons why Limpkins haven't made the journey here before.

If

lack of snails was a factor...where they're here now. But, if there are

other environmental reasons (such as temperature)

the Limpkins may not

stay. I hope they do.

Go

back to my home page, Welcome

to rickubis.com

Go to

the RICKUBISCAM

page.